Gateways and gatekeepers: How Google’s mistakes can still affect web3

Operating an IPFS HTTP gateway in a web2 world

NFT.Storage launched our IPFS HTTP gateway in early March, which has largely been a success - it is currently performantly providing 25 to 30 million reads of NFTs per day without users needing to install any specialized software, supporting dozens of NFT marketplaces and projects.

However, it has not been completely smooth sailing. This post discusses pain points that the NFT.Storage team has faced since launch due to “gatekeepers” of the web today. This has included outages caused by Google Chrome Safe Browsing on two separate instances, where false positives caused them to flag the entire gateway domain to effectively the entire web browsing population for 4+ hours each time (blocking users from accessing ~5,000,000 NFT requests in each instance), as well as smaller instances where security vendors flagged the domain, causing issues for users from unpredictable places. In these situations, generally we have seen these parties have good intentions, but bad outcomes in practice simply due to their level of concentrated power in the web. We share our experiences to open a dialogue across the IPFS ecosystem and the powerful entities that control the web experience today, like browsers, security vendors, and large websites.

IPFS HTTP Gateways: A primer

IPFS HTTP gateways are a critical piece of infrastructure to bridge the current web to a more secure, performant, and decentralized version. They allow users that are not running their own IPFS nodes to access data off the public IPFS network via standard HTTP, meaning that web browsers and common tools and applications can easily read data whose IPFS content IDs (CIDs) are being broadcasted to the public network. There are many public gateways today being run as public services, many more being run as a paid service, and likely many more to come.

Users request content from an IPFS HTTP gateway by including a CID in their HTTP request. Since CIDs are a hash of specific data, if the data is broadcasted to and accessible by the gateway, the gateway can get that specific data from the network no matter where it sits.

It’s not perfect - for instance, gateways are still centralized infrastructure, meaning they will inevitably face outages. However, because content is still requested via their unique CIDs, you end up with the ability to not only request given content from any gateway, but you get other benefits, like the ability to access cached copies of a given piece of content from it being cached just once. Gateways are a viable decentralized solution in a Web2.5 world.

Gateways and malicious content

As long as the web has existed, there has been malicious content on the web, with bad actors looking to exploit unknowing (or, sometimes, knowing) users. For IPFS gateways, this problem is handled quite elegantly given the nature of CIDs - if a gateway knows to block a given CID, it knows to never serve the content no matter who is requesting it or where it might sit on the IPFS network. It’s similar to the technique that some virus scan software uses locally, but applied to content on the web.

One way this is used by gateways is in a “Bad Bits” Denylist that takes reports of malicious CIDs and makes a publicly available list that can be securely integrated with a gateway, so that gateway can block requests for those CIDs. Further, gateways can serve content using the CID in the gateway URL’s subdomain. This allows any domain-level blocking done by folks downstream of the gateway, like web servers, security providers, and browsers, to be isolated to specific subdomains associated with bad CIDs. This makes it safe to block isolated CID without blocking the entire gateway, making sure the entire gateway service is not taken down by malicious content uploaded by a single bad actor.

Getting deleted from the internet

NFT.Storage launched our gateway in early March. Adoption accelerated rapidly, with 25 million weekly requests already by the second week. Folks minting Solana Metaplex NFTs (which require HTTP URLs) like Magic Eden started using nftstorage.link URLs that contained the CIDs of the relevant NFT content. Some of the latest numbers include over 155 million requests last week for more than 1000 TB and a >70% cache hit rate.

We also quickly found oversized hammers from the web2 world that were able whole business sectors offline. Despite the proactive security measures in place for gateways, the structure of our web today led to Google alone causing two major service disruptions for us, dozens of our users, and ~10,000,000 of their end-user requests, as well as an ongoing game of whack-a-mole with smaller security vendors.

Incident 1: Google Safe Browsing

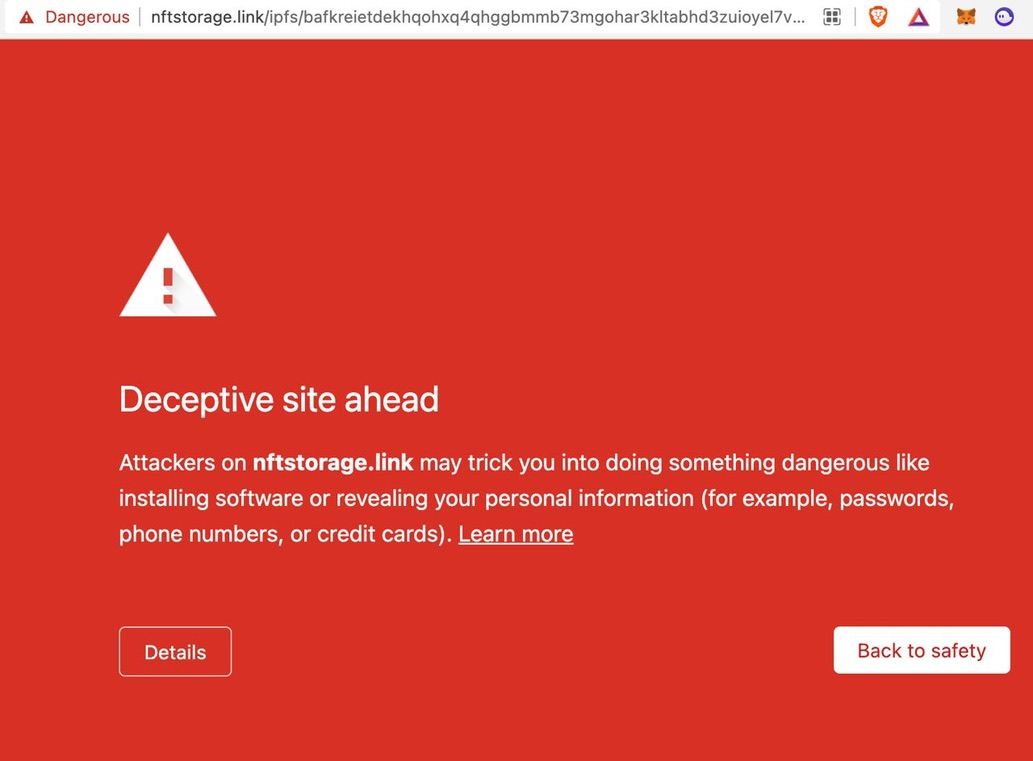

On March 29, 2022, user reports started coming in that all content accessed via nftstorage.link through any major web browser would result in a Google Safe Browsing warning. However, in all reported cases, the content was harmless - NFT JSON, PNGs, JPEGs, and the like.

Screenshot from an NFT.Storage user who was trying to access an NFT metadata JSON file.

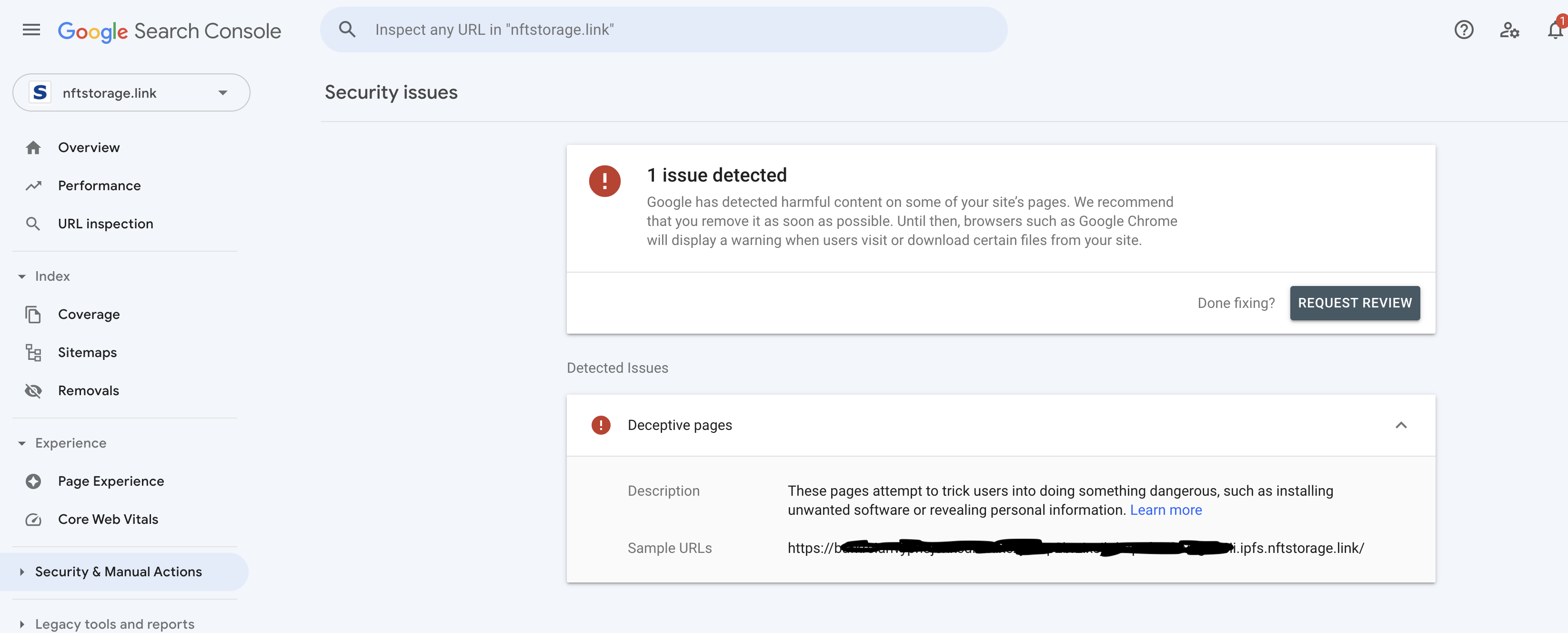

After some furious searching (and guidance from random help websites), we learned that we had to log into Google Search Console to learn more about why our domain was blocked. The console was clear that a specific CID was the culprit, and we verified that the content was a phishing form. However, even after immediately blocking this CID all we could do was “request a review” that could take up to 72 hours. This was extremely opaque, without a request tracker or even an email telling us our request was in review.

You can only clear up false positive reports in Google Search Console, and the experience does not match the needs of the user urgently trying to clear their domain.

And it was quickly evident that many browsers and services used this list - not just Chrome, but Firefox, Twitter, Phantom Wallet, and more! So given that being on this list resulted in effectively a complete outage of nftstorage.link, we couldn’t wait 72 hours. We tried other methods to get back online, like having nftstorage.link directly CNAME to the dweb.link public gateway, though this did not work because nftstorage.link was blocked at the domain level.

Our team and other members of the IPFS ecosystem tried backchanneling through every Google person we collectively knew, but this happened at a rather inconvenient time - late at night Pacific Time and before the workday had started in Europe. After a few hours, we finally got indirectly into contact with the responsible team. They took us off the blocklist, and we received email confirmation that our Google Search Console request had been accepted. Our backchannel contact told us that the team promised to never block the entire domain moving forward, but just the relevant subdomains corresponding with the malicious content, which we took as a positive outcome.

In the meantime, an estimated ~5,000,000 requests were blocked from the gateway. This was especially alarming for folks in Solana who had NFTs that were minted using nftstorage.link, and they couldn’t access them in their wallets, causing fear of a rug pull.

We later learned that we were not the only ones who have suffered from this exact issue - Google opaquely blocking their domain without timely or transparent recourse. This Hacker News thread contains various thoughts on the topic, with the general conclusion that there is little an individual can do.

Incident 2: Whack-a-mole with security vendors

Since this initial incident, there have been some other isolated reports of users being blocked from accessing harmless content through the gateway. Sometimes, it’s easy to identify why - for instance, Avast Antivirus was flagging all nftstorage.link domains. In other cases, it’s far more opaque, like SSL HTTP errors being returned without any further explanation. And sometimes, there is a variety in behavior, like subdomain-based and path-based CIDs giving different results. Overall, we have received reports of isolated issues due to ISPs, anti-virus software (but inconsistent across users with the same software, like Windows Defender), VPNs, and more.

Adding to further trouble is that sometimes users experience these errors through other tools, meaning it can be difficult to debug. For instance, when a user’s wallet cannot show their NFT because of these issues, we don’t get a clear error message. In fact, sometimes it’s not even nftstorage.link at the root cause - our team spent over a week debugging errors for the dweb.link public gateway.

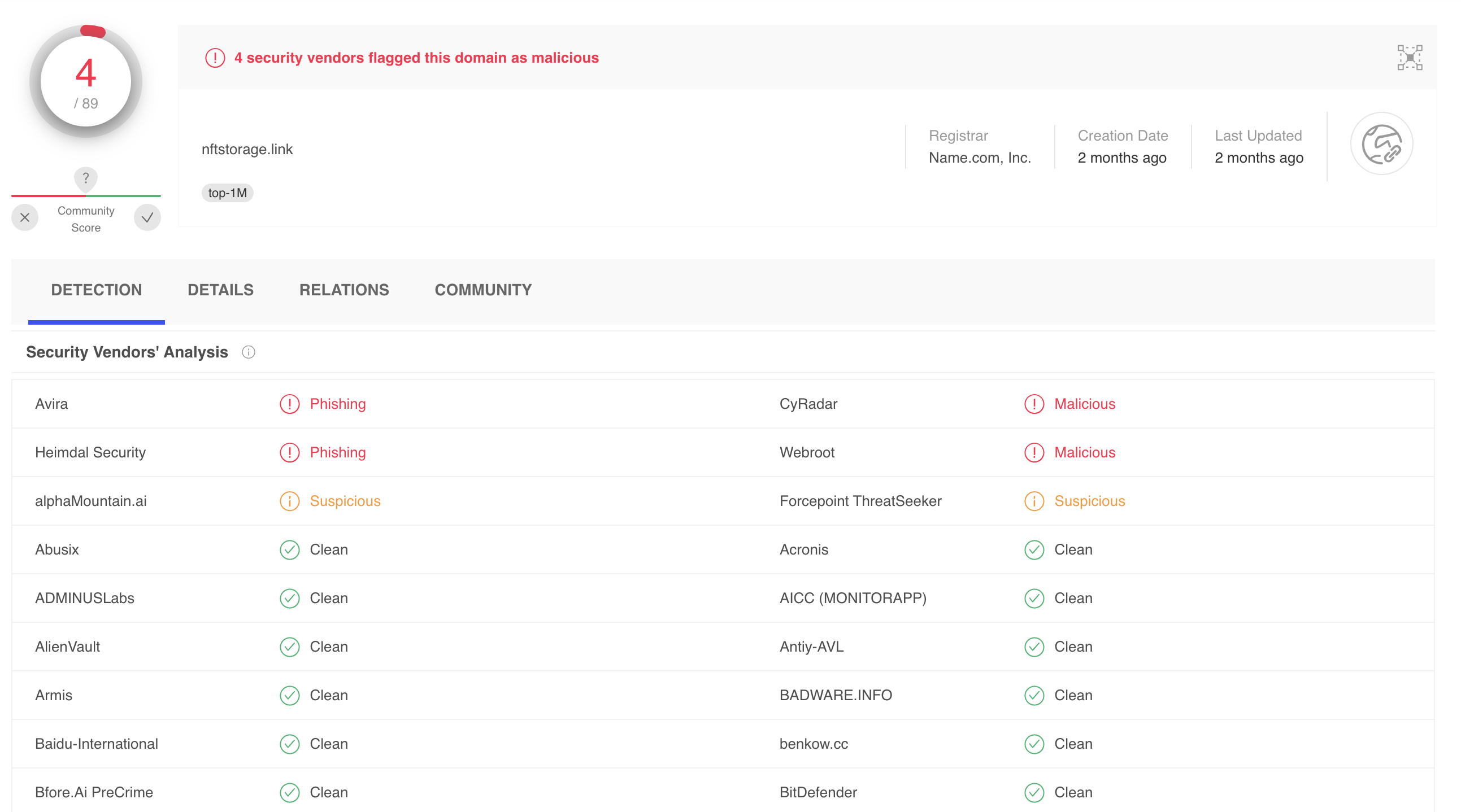

To try and isolate the individual software vendors that have been creating these issues, we looked at websites like Virus Total to tell us which security vendors had flagged nftstorage.link or ipfs.nftstorage.link (confusingly, a different subset of vendors marked each of these domains as suspicious) and reached out to these teams letting them know there were false positives. Folks like Avast were very responsive, and immediately resolved these issues. Others, like Webroot, pushed back without any explanation or an easy opportunity to continue the dialogue. Still others never responded even after multiple follow-ups. Ultimately, by not resolving our requests, these software vendors are ultimately increasing their false positive rate by blocking all URLs with gateway domains.

Virus Total was handy in identifying which security vendors had flagged nftstorage.link, though not all of these vendors were willing to even have a discussion.

One observation was that these vendors likely used Google’s list to inform their lists (explaining why some of these lists had marked nftstorage.link as suspicious). In turn, ISPs, VPNs, and others use these security vendors’ lists, with some asynchronicity (for instance, the ISP Swisscom had blocked all nftstorage.link domains, but when we requested they remove the domain from their denylist, they complied, saying that it had been taken off the 3rd party list they use). In every case, the entire dependency chain was extremely opaque.

These sort of reports have subsided, for now, though we definitely welcome any security vendors to take a look at how they’re handling nftstorage.link and other gateways to make sure they don’t get caught in this false positive net.

Incident 3: Google...again

On April 21, 2022, Google Chrome Safe Browsing again blocked the entire nftstorage.link domain, leading to all the same downstream effects as before. We were understandably shocked and concerned by this, as they had assured us that the entire domain would never again be blocked.

This time, we had a more difficult time getting into contact with the relevant team through backchanneling. We followed the same protocol as before, but the problems persisted beyond a few hours, so we publicly tweeted out about the issues.

The entire (nftstorage . link) gateway domain is currently blocked by @googlechrome despite the flagged content isolated to one CID subdomain. We had previously been assured by @Google that this would not happen. We are working to resolve this. #centralization #Web2 (1/2)

— NFT.Storage (@nft_storage) April 21, 2022

When this second round of issues were not resolved in a timely manner, we let our users know and called Google out.

A little bit later, the issue had suddenly resolved itself - minus URLs with the specific malicious CIDs, but the gateway was unblocked. We were mostly relieved, but found it curious that we did not receive a notification from Google Search Console this time that our request had been accepted.

The next day, one of our Google contacts let us know that the relevant team had admitted that they had put in a bad regex statement. We’ve all been there before, and we were thankful that this confirmed the team's intent was to make sure the entire domain wouldn't ever get blacklisted again. However, but it once again did show the inherent issues of one party having so much power (why wasn’t there better testing? why was the resolution process so opaque?).

Suggestions for web operators

In just over a month of operation, there are millions of requests for nftstorage.link a day. And until IPFS nodes get wider adoption in browsers, mobile, and other places, one would not be surprised to see hundreds to thousands more gateways appear for different purposes. There’s a ways to go before we decentralization reaches enough of a critical mass to ensure these issues don’t happen again for the average web user. For now, we detail some advice and conversation topics to ideally kick off the dialogue for the various groups involved.

Gateway providers

If you’re a gateway provider, we recommend implementing the security measures we outlined above, namely using the Bad Bits Denylist to automatically block the encrypted CIDs from your gateway, and making sure that security providers have an easy time blocking bad URLs by routing all requests to use subdomain-based CID requests.

Otherwise, if your gateway is supposed to be used for specific content, limit content to decrease the surface area of malicious content being served through your gateway. Potentially most relevant: if website hosting is not useful, block the text/html response type – it will remove ability of hosting phishing static HTML pages on your gateway. You can also consider blocking Javascript content, cookies, web API access, etc.

Also potentially useful if you want to host static HTML but don’t want to allow Javascript or cookies is to return additional headers with HTTP responses (though this doesn’t protect against most basic phishing campaigns):

Clear-Site-Data: "cookies", "storage": Only purge cookies, keep “cache”Content-Security-Policy: Established way of disabling JS and various security featuresPermissions-Policy(previously namedFeature-Policy): Another way of disabling various APIs and behaviors, though WIP by Google

You can also try to get your gateway on the Public Suffix List. The Public Suffix List is “a cross-vendor initiative to provide an accurate list of domain name suffixes.” This makes it less likely security vendors block the your entire domain, and gives something easy to point to in the case of false positives. We have not yet been successful adding nftstorage.link (request), but dweb.link was previously accepted.

Security vendors and browsers

If you are a browser or security vendor that flags malicious content, we recommend being transparent about how you categorize domains, and ideally include an IPFS gateway categorization. This shouldn’t be too different than how many of these vendors already handle peer-to-peer filesharing websites or websites that publish user and developer content, which face some of the same fundamental problems. In fact, in our experience, security vendors that had categories representing these types of websites were the fastest to resolve our false positive requests for nftstorage.link.

Further, if you are a vendor or browser that uses a 3rd party blocklist like Google Chrome’s, we advise being careful when the list tells you to block an entire domain. By having your own categorization for websites that serve user uploaded content, you can check against your own list when the 3rd party list tells you to block an entire domain, and you can keep the power of these 3rd party lists from mistakenly taking down entire services in check.

In either case, having a well-advertised, transparent, and timely review process for false positives is potentially the best thing you can do to benefit the web. Even with the best of intentions, mistakes will almost certainly happen. Taking your power, and the associated responsibility, seriously, will lead to a healthier web.

Decentralizing the gatekeepers

Ideally, the ultimate state of the web involves decentralization to a much deeper level than today. Technologies like IPFS reduce the ability for gatekeepers to disrupt key portions of the web, regardless of their intentions. Realistically, it will take time and energy to get there, though with more people building and adopting web3 solutions, things are trending in the right direction. In the meantime, we hope that the case of IPFS HTTP gateways shows a promising path to further decentralization of web infrastructure, and where internet gatekeepers need to improve to enable this progression.